Hajj: how globalisation transformed the market for pilgrimage to Mecca

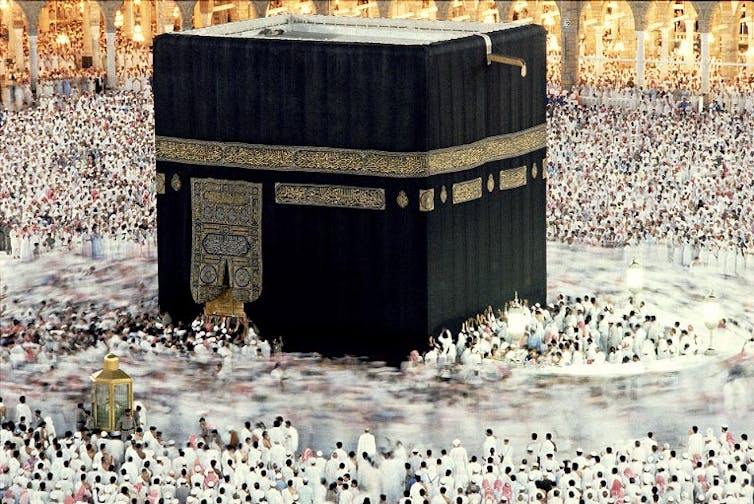

Seán McLoughlin, University of LeedsMore than 2m Muslims are currently gathering in Mecca ahead of the annual Hajj, which begins on August 19. As long as they are fit and financially able, the pilgrimage is an obligatory act of worship that followers of Islam owe to God once in their lifetime. Reenacting the faith-testing ordeals of Ibrahim (Abraham, the Biblical founder of monotheism) and his family, Muslims believe that an “accepted Hajj” will cleanse them of all their sins. Their hope is to return home as pure as the day they were born.

But until the introduction of modern transport systems, most Muslims beyond the Arab world had little expectation of completing this fifth and final pillar of Islam. Before the mid-1950s, the number of overseas pilgrims rarely exceeded 100,000 and modern Saudi institutions were still developing. Yet by the early 2000s, the total number of Hajj pilgrims had passed the 2m mark, reaching a recent peak of just over 3m in 2012.

New opportunities for pilgrimage in the jet age have put immense pressure on the infrastructure of Mecca. Hundreds have lost their lives during periodic disasters including fires and stampedes, most recently in 2015. Undoubtedly, the Saudi authorities have invested huge sums in continually seeking to improve facilities and the overall management of the Hajj. Hajj organisers and guides I have interviewed compare overseeing the pilgrimage to hosting the Olympics every year.

Read more: Here's how to make the Hajj safer – by better understanding crowd psychology

But the kingdom’s Vision 2030, published by Crown Prince Salman in 2016, underlines that the Islamic tourism market has a significant role to play in diversifying Saudi Arabia’s non-oil-based economy. While the strategy is focused mainly on the Umrah (the year-round, non-obligatory minor pilgrimage), US$50 billion investment in new transport and other infrastructure also aims to double the size of the Hajj by the end of the next decade.

Supply and demand

A look at Hajj-going among British Muslims in an age of globalisation underlines the growing role of the market for religious tourism in shaping the organisation of the pilgrimage. At an industry event I attended earlier this year, The Council of British Hajjis, suggested that this niche sector of the UK economy is worth around £150m (£310m including Umrah).

Unlike all Muslim-majority nations, Muslim minorities in the West are not restricted to a Hajj quota of 1,000 pilgrims per million of population. Relatively prosperous, literate and increasingly socially mobile, they are generally free to perform the pilgrimage at a time of their choosing. Pilgrims in the West are also often younger than those in the rest of the Muslim world. The number of British Muslims performing Hajj each year rose from 759 in 1968 to around 25,000 by the mid-2000s – about twice the rate of UK Muslim population growth for the same period. About 100,000 now go annually for Umrah.

In the West, secular governments play no direct role in organising Hajj. Until the 1990s, there were also just a few companies formally arranging Muslim pilgrimages in Britain. So, most UK Muslims travelled to Saudi Arabia as individuals or as part of a small community group. But during the early 2000s, in a bid to improve services to pilgrims, the Saudi authorities insisted that anyone organising Hajj should form a registered company and be properly licensed. By the mid-2000s, they also made buying a “package” from one of these organisers the only way for Muslims in the West to perform Hajj.

Rising prices

Today there are around 117 UK Hajj organisers licensed by Saudi Arabia. Each is responsible for their own annual quota of 150-450 Hajj pilgrim visas. British Muslims now have plenty of choice in terms of package options. But UK pilgrims wanting to perform Hajj in 2018 probably spent as much as £5-6,000 on their package. At an industry event last spring, I was told that a top company selling half their packages for £9,500 per person sold out in six weeks. Even an “economy” Hajj this year cost more than £4,000. Overall, the cost of Hajj-going has increased by around 25% in recent years.

Long-established pilgrim welfare charities such as the Association of British Hujjaj (established 1998) complain that high prices reflect UK organisers’ profiteering. But the bigger picture is that the restructured Hajj industry in Saudi Arabia is increasingly privatised and commercialised. The 2-3m Muslims arriving to the city of Mecca for one key week in the calendar create a huge demand for travel, accommodation and other services. And for all its investments in pilgrimage infrastructure, the Saudi government does not control the pricing of flights, rents and so on. Certain local subsidies are being reduced and Saudi VAT and municipality taxes have increased recently, too.

Members of the UK’s newly formed Licensed Hajj Organisers national trade association (established 2016) are in a risky business. In the tourism industry, payments are usually made in arrears, but UK Hajj organisers often make large down payments before packages are even sold. And because they lack the bargaining power of large Muslim governments, Hajj organisers in the West can pay a premium for some services. Political and economic instability, such as wars in the Middle East and the negative impact of Brexit on the pound, also affect pricing.

Regulation and the future

The new leadership of Licensed Hajj Organisers are keenly aware of the complex issues faced by the Hajj and Umrah industry. Few UK Hajj organisers can sell their entire quota without maintaining relationships with networks of sub-agents. Spot checks for “Hajj fraud” by Trading Standards suggest that long selling chains and a lack of proper documentation can encourage “over-selling” and even criminal scams.

That there is a new willingness in the trade to hold fellow organisers to account in this regard is clear from a new code of conduct launched by Licensed Hajj Organisers before Hajj this year. At the same time, many Hajj organisers still argue that the European Package Travel Regulations, intended to regulate “package holidays”, cannot account for the logistical and business complexities of Hajj.

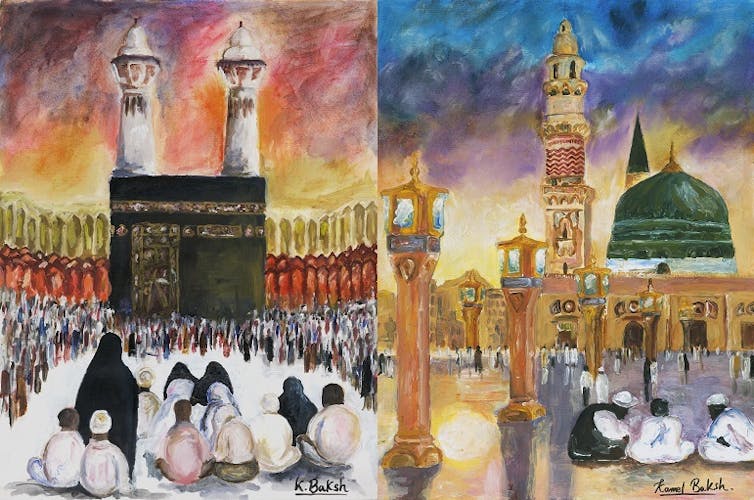

Transformations in the organisation of Hajj-going in Britain represent only a local case study of challenges the Hajj and Umrah industry is facing worldwide. Piety and commerce have always existed cheek-by-jowl in Mecca. But the development of a consumer-capitalist model of religious tourism on the scale envisaged by Saudi Arabia is unprecedented. Great chains of buying and selling as well as believing now connect Muslims to the birthplace of Islam. But there are major issues to resolve across quite different regimes of regulation. For some, this suggests a need for greater international governance of the Hajj and Umrah.![]()

Seán McLoughlin, Professor of the Anthropology of Islam, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.